20-04-15 // MONU #22 – TRANSNATIONAL URBANISM

(browse the entire issue #22 on Youtube)

Liberté, Digitalité, Créativité – Interview with Jean-Louis Missika by Beatriz Ramo and Bernd Upmeyer; On Home, in a World of Non-possession by Merve Bedir; Rescaling Transnational Geographies by Antonio Petrov; Third Form Cross Border Cartography – A Middle Eastern Exostructure by Maier Yagod; Transnational Urbanisms of Asylum Trajectories by Kolar Aparna; Global Towns in the New Copperbelt by Justin Hui; Harmony Through Commerce – How Yiwu Embraced Islam by Laura M. Henneke; Madgermanes by Malte Wandel; Binational Urbanism – On the Road to Paradise by Bernd Upmeyer; Zeeuws Vlaanderen, NL/BE: The National Border as Catalyst for a Transnational Periphery by Pepijn Bakker and Rutger Huiberts; Magical and Mediated: Transnational Urbanism in Quiapo, Manila by Thomas Mical; Hidden Space – Social Space – The Spatiality of Temporary Migration Between Home and Host Countries by Dalal Musaed Alsayer; Actor Map of Korea – And Spatial Scenarios of Transnational Networks by Yehre Suh; Transit Space in The Straits Megacity Region by Agatino Rizzo; Discrepant Sea by Kyle Hovenkotter and Trevor Lamphier; The Urban Pier – Exchanges of Work by Zoé Renaud; Informal Control – Interview with Ulf Hannerz by Bernd Upmeyer; New Prospects for Urban Planning by Giovanni Matteo Cudin; Humanitarian City by Paul Currion; United Sustainable Urban States by Matilde Igual Capdevila

To prepare our cities for the emergence and growth of transnational lifestyles we need to invent new urban and architectural forms that are adapted to these new ways of life. This is what the French sociologist and assistant Mayor of Paris, Jean-Louis Missika, emphasized in an exclusive interview with MONU entitled “Liberté, Digitalité, Créativité” on the topic of “Transnational Urbanism”. This new issue of MONU focuses on the impact of transnational processes on cities in general and the consequences of transnational relations between individuals, groups, firms, or institutions for cities in particular. We deemed it necessary to dedicate an entire issue to the phenomenon of transnationalism in relation to the city, to architecture, and its influence on cities in spatial as well as social, political, economical, and cultural terms, as these days, more than ever before, and due to the development of technologies that have made transportation and communication infinitely more accessible and affordable, people can create and maintain multiple links, networks, and interactions across the borders of nation-states. In that regard, Missika stressed furthermore the importance of an open government: open to innovation and to innovative projects in which a lot of different people have to work together and citizens participate in planning processes. Only then can transnational urban landscapes that support transnational urban lifestyles be created as “super geographies”, as Antonio Petrov puts it in his contribution “Rescaling Transnational Geographies”, moving architecture beyond geographical constraints, borders or boundaries and support the flow of people and information. In such urban landscapes “imagined communities” without the need for physical or territorial contact and a communal consciousness can emerge independently – that is: characterized by small everyday gestures, acts, practices, and exchanges between individuals, as Kolar Aparna states in her piece “Transnational Urbanisms of Asylum Trajectories”. Under these conditions transnational places can be created in cities where people can feel at home no matter where they come from, as Laura M. Henneke argues in her contribution “Harmony Through Commerce – How Yiwu Embraced Islam”. Due to globalization urban spaces are emerging that are witnessing increasing intensity of use, mixed desires and mixed codes, cross-fertilizing urban sites with an enlarged spectrum of identities as Thomas Mical argues in his article “Magical and Mediated: Transnational Urbanism in Quiapo, Manila”. Kyle Hovenkotter and Trevor Lamphier, in their contribution “Discrepant Sea”, define the architectural style that appears under such transnational circumstances as characterized by duplicity, invisibility, and temporality, in contrast to the technological fetishism, transparency, and material honesty that distinguished the first international style. Nevertheless, such multiple identities and temporalities, according to Ulf Hannerz – a pioneer in urban and social anthropology whose research on culture in the age of globalization suggested as early as the 1960s the dynamic, flowing, creative, and continuously changing character of the process – will not necessarily lead to identity problems of urban spaces, since the diversity of neighbourhoods will take care of this, as he explained to us in another interview entitled “Informal Control”. While trying to demystify culture, something he sees as ‘processual’, he considers human beings to be agents who keep culture going by doing, watching, listening, and learning. Understanding “Transnational Urbanism” as an urban culture that needs to remain in motion continuously, reinvent itself perpetually, in order to sustain itself, might lead to the fulfilment of our desires and cosmopolitan visions for a better future, and a world without borders, as Matilde Igual Capdevila dares to dream in her piece “United Sustainable Urban States”.

(Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, April 2015)

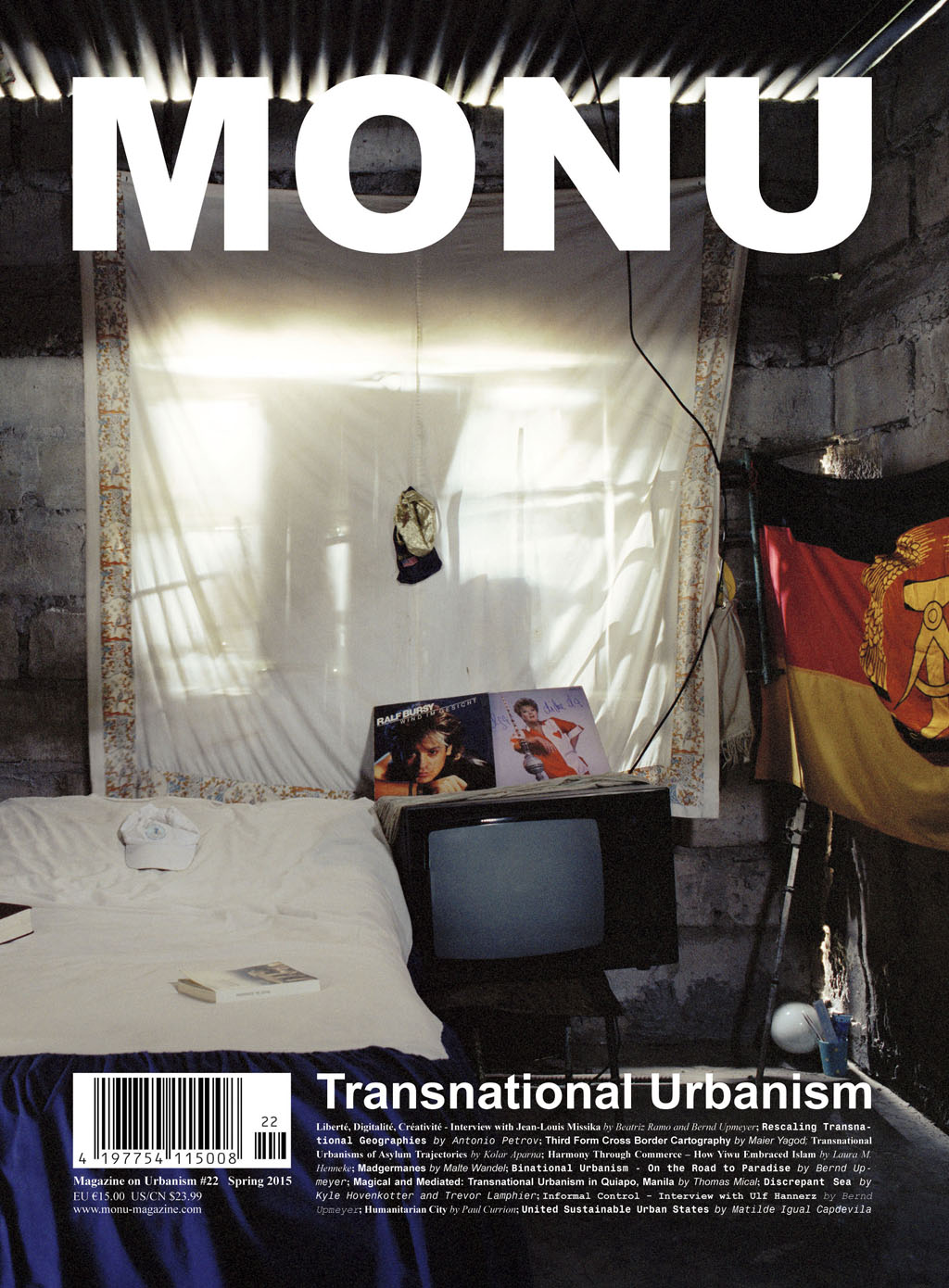

(Cover Image: “Sleeping room of Nelson Ernesto Monheguete with cooker, TV and other relics from the former GDR” from Malte Wandel’s contribution “Madgermanes” on page 52. Photo is ©Malte Wandel.)

Find out more about this issue on MONU’s website.