22-02-16 // SPLIT IDENTITIES – A REVIEW OF BINATIONAL URBANISM BY MATAS ŠIUPŠINSKAS

Cover of Binational Urbanism – On the Road to Paradise, Photo: Matas Šiupšinskas, @Matas Šiupšinskas

Mass migration is not a modern phenomenon. From crusades to slave trade, people have been displaced or have been displacing themselves in order to reach new territories of opportunity. Even if migration has recently become a huge problem and is seen only negatively, some voices express different kinds of opinion. In a contemporary global economy migration does not always end up with permanent displacement, and because of that it becomes possible to look into migrants differently. So what kind of new perspective opens up by this twist of perception?

Bernd Upmeyer argues that in the recent decades a new phenomenon appeared: binational urbanism. A binational urbanist is constantly living between two different cultures and two different sets of urban landscapes. He is not a migrant, but an ultimate commuter who travels not between home and work place, but between two identities of its own, between two cultures from which he breeds. This kind of commuter is presented as the urban avant-garde and not as a victim of faith and context. In Binational Urbanism the author explores not only the lifestyle, but also the whole mechanism of such movement.

You might know Bernd as an editor-in-chief of the MONU – magazine on urbanism. His book follows the conceptual pathway of the magazine by using simple, restrained design layouts spiced with bold info graphics. Even the title of the book follows the naming pattern of its predecessor – MONU. All the visuals (charts, maps and collages) of the book are designed by Bernd and his Bureau of Architecture, Research, and Design (BOARD). It looks like the author was reaching for full control of the final result, so therefore the piece should be evaluated in its entirety.

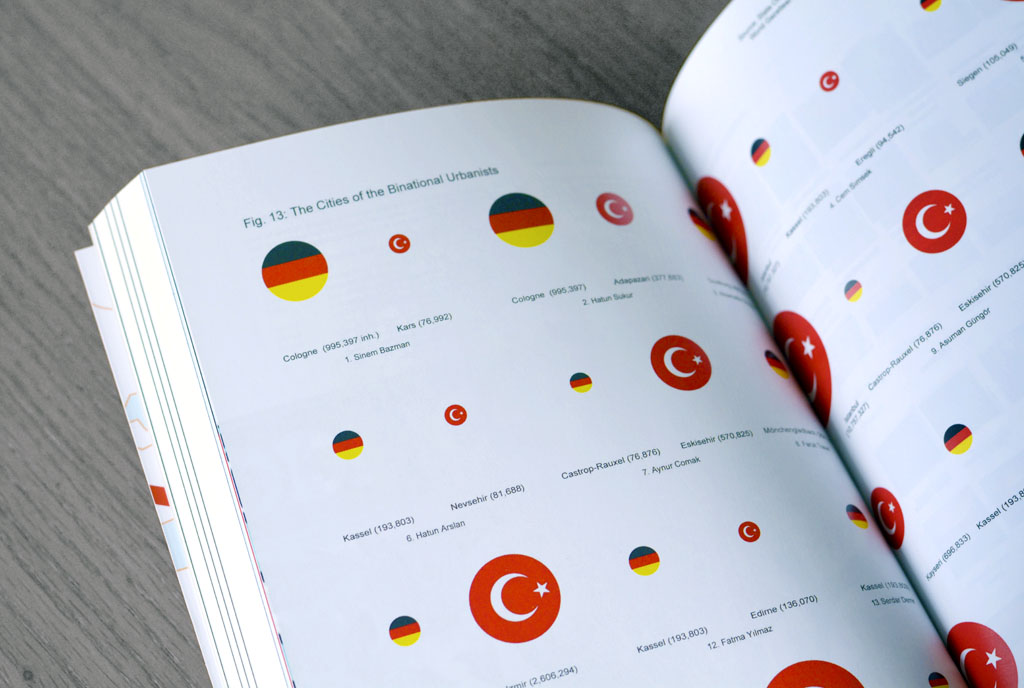

Page 124 of Binational Urbanism – On the Road to Paradise, Photo: Matas Šiupšinskas, @Matas Šiupšinskas

The book is devoted to a specific case study of binationalism and its relationship to urbanity: a Turkish community in Germany. However, Bernd’s insights are quite universal. Since the methodology is clearly structured and easily replicable, it can be applied to most countries and to different kinds of communities. The author’s primary interest is the urban aspect of binationalism, but this idea evolves and more layers of the phenomenon are covered. Urbanity is still playing a big role in the book, but a much wider perspective about links between physical and cultural spaces are drawn.

The book’s main question is based on the motives behind binational urbanism and how it affects human life. It analyses why people choose to leave the cities of their origin and investigates why they decide to come back again and again. Reasons behind this oscillation are economical, but also deeply personal. So in search of answers Bernd carried out 20 interviews with people of Turkish origin of different gender, age and occupation. This ability to break the complicated topic down to the personal level is one of the greatest qualities of the book. The interviews help to describe binational urbanism in a less abstract but very personal way, something that movies sometimes manage when focusing on a few individuals that represent a huge group of a major historical event.

All in all it is a book that provides a glimpse into an interesting urban phenomenon – the way of life of extreme commuters. Simplicity that appears through the focus on individuals and their lives makes the topic graspable, less abstract and more real. Its content is clearly structured and valuable not only for researchers, but also for architects and urbanists who are interested in thinking beyond their usual profession; and of course for everybody who is interested in urban topics and contemporary culture. It is also a good read for those who follow MONU – magazine on urbanism. I hope that after this introduction to the topic, urbanists would continue exploring it and start imagining cities that adopt binational urbanism and the way of life of binational urbanists.

P.S.: Those who have read the book To Kill a Mockingbird probably remember the character of Calpurnia. She was an African-American maid who acted differently at work and among her own community. She is an example of such a double identity, which is unavoidable when displacement happens. The paradox of modern life is that most of us, from laborer to venture capitalist, are like Calpurnia – living a double life between our origins and our current condition. From time to time we travel back – physically, socially or in our dreams – and soon we will leave again, just to continue this eternal journey between present and past. Most of us already are bi-national, bi-regional, bi-city urbanists in one way or the other, and that is why it is important to talk about modern forms of migration and how it affects our life and our cities.

Matas Šiupšinskas is an architect. He researches on the history of town planning, mass housing, housing typologies, urban morphology and Soviet architecture. He occasionally writes for popular and scientific magazines (Volume, Monu, Archifroma, Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, Echo Gone Wrong etc.). Currently he is a PhD student at Vilnius University researching on the urban phenomenon of collective gardens in Soviet Lithuania and its contemporary transformation.

This review was first published by A Daily Dose of Architecture on February 16, 2016.