31-10-18 // LATE LIFE URBANISM

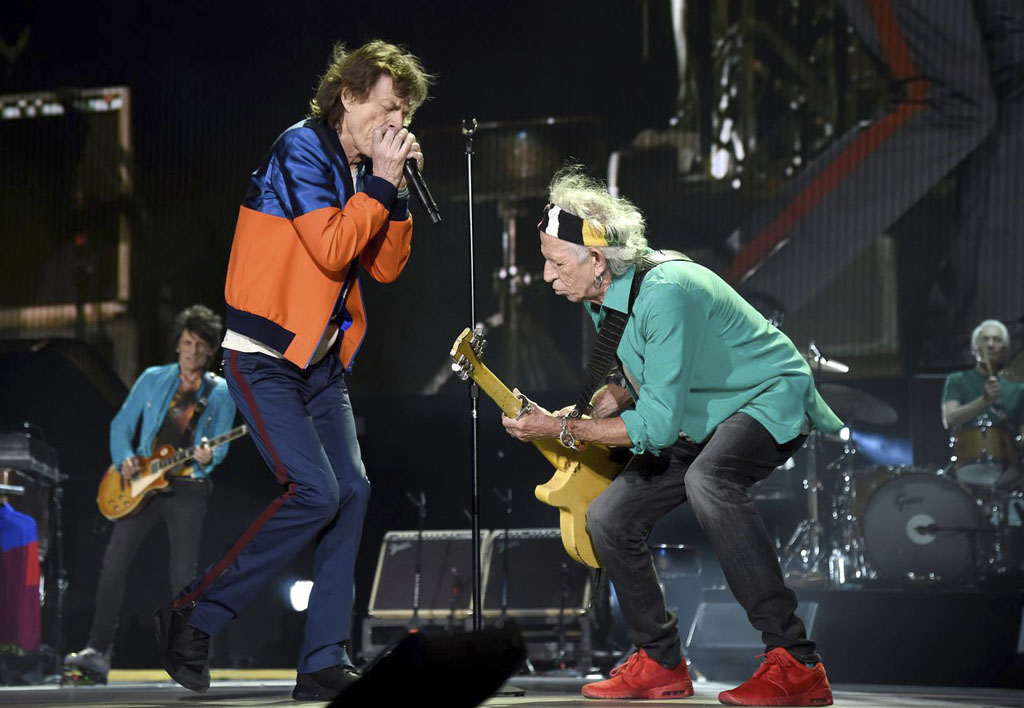

Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones performing at the Desert Trip Music Festival in California in 2016, photo by Kevin Mazur, ©Getty Images

Late Life Urbanism

By Bernd Upmeyer

When I was studying in the late 1990s and early years of the new millennium, a very common task that was set for us by our professors was to design a retirement home. Although I did not take part in these projects at the time, I understood the necessity to prepare students for a future in which our societies would become increasingly older due to declining fertility rates and rising life expectancy through which the number of people aged 60 years and over had multiplied since 1950, reaching hundreds of millions worldwide. Accordingly, it was good that there was a growing focus on people in their later life and their way of living, which has ever since led to a lot of research, both practical and theoretical. However, when I was recently confronted personally with the current state of care for the elderly, I realized that there is still a lot to improve, invent, innovate, and discuss when it comes to the way old people in the need of care live, particularly in a society that is ever more individualized, lacking traditional family models in which such care used to take place. That is why we want to dedicate an entire new issue of MONU to a topic that we call “Late Life Urbanism” and which we want to investigate on an architectural level, but on the level of the city too.

I believe that shared and communal forms of living have an enormous potential that needs to be explored further. As Yasmine Abbas, Lara Jaillon, Thomas Watkin, and Onnis Luque explained in their article “Two Generations Together” in MONU #18 communal living of different generations – with accommodations shared by elderly and younger people – might be an answer to present urban challenges that appeared due to increasing social fragmentation, weak or fragile economies, and the burst of the housing bubble that pushed many countries to the edge of acceptable standards of living. Another great possibility might be offered by technology, which the Rotterdam-based collective Cookies demonstrated in their article “A Nice Normal Little Village” in MONU #24, showing how the digital machines of today might articulate our domestic lives of tomorrow, based on their research into a care facility for elderly people on the outskirts of Amsterdam. Ideally, there will be progressively more clever technology (just think of smartphones, social media, connected homes and autonomous cars, etc.) to help the oldest group in our society make the most of the final stage of their lives, enabling them to age at home and retain as much autonomy as possible. But the organisation and shape of the more common solutions for old people and their way of living that are usually provided by retirement homes, nursing homes, retirement communities, forms of assisted living, independent senior living, etc. should be re-thought and analyzed creatively too, both in terms of architecture and the urbanism they create.

Nevertheless, since people such as Mick Jagger have made it obvious that being in your seventies – as if arthritis and dementia do not exist – does not necessarily mean that you become a passive, worn-out, sick, isolated, and dependent member of society, but might instead have the time of your life, cities and buildings need to adapt to the consequences that this brings too. Today’s 65-year-olds are in much better shape than their grandparents were at the same age. And if life can be that great in later life, Brian May of Queen must have been wrong when he asked: “Who Wants to Live Forever?”, because in that case most of us do. There even have been speculations that a longer life expectancy will change how we occupy ourselves, how we live, and what careers we choose, because during the course of a longer life one profession might no longer be enough and people might wish to start from scratch in their fifties or sixties, having maybe forty years ahead, and enter entirely new directions, which will make “old” people much more mobile, impacting the dynamics of cities. Therefore, our built environment needs to keep up with the longer and more productive lives of people since those new “young old” are in relatively good health, often still work, and have money to spend.

These are just a couple of thoughts about the topic of “Late Life Urbanism” that we consider a very urgent topic, necessary to debate and examine. What we are interested in especially is the way of living and the way we house ourselves in a time when our societies are increasingly populated by people over 65, which calls for a fundamental rethink of life conditions and a new look at the assumptions around ageing and the planning of cities needed for this phenomenon. Thus, this new issue of MONU will have a clear focus on housing for people in their “late life” and its consequences for and relations to cities.

Title: Late Life Urbanism

Author: Bernd Upmeyer

Date: October 2018

Type: Call for Submissions, MONU #30

Publications: MONU – Magazine on Urbanism

Publisher: Board Publishers

Location: Rotterdam, The Netherlands