14-10-19 // MONU #31 – AFTER LIFE URBANISM

(browse the entire issue #31 on Youtube)

Democratizing Death – Interview with Karla Rothstein by Bernd Upmeyer; The Cemetery of the Living by Miguel Candela; With Seven Bodies in My Backyard by Omar Kassab and Mostafa Youssef; Constructing Memorial Poles as Monuments by David Charles Sloane; Ghost Life Urbanism by Jérémie Dussault-Lefebvre and Sébastien Roy; Death and Burial: In the Past Lies the Future by Carlton Basmajian and Christopher Coutts; Beyond the Grave: Conscious Consumption in Life and Death by Sybil Tong; Cemetery and Crematorium Futures by Julie Rugg; The Silent City by Nicole Hanson; You Could Be Compost by Katrina Spade (Recompose); Mourn by Nienke Hoogvliet; Rest in Pixels – Interview with James Norris by Bernd Upmeyer; Watching the Wakes of Strangers through the Internet by Andréia Martins van den Hurk; Suburban Halloween Decorations by Cameron Jamie; Set in Stone: Humans and Barre Granite by Monica Hutton; Claim Domain: An Urban Case for Burial by Anya Domlesky; Exuberance and Resistance by the Dead by Bruno De Meulder and Kelly Shannon; Coexisting: A Matter of Life and Death by Elissaveta Marinova

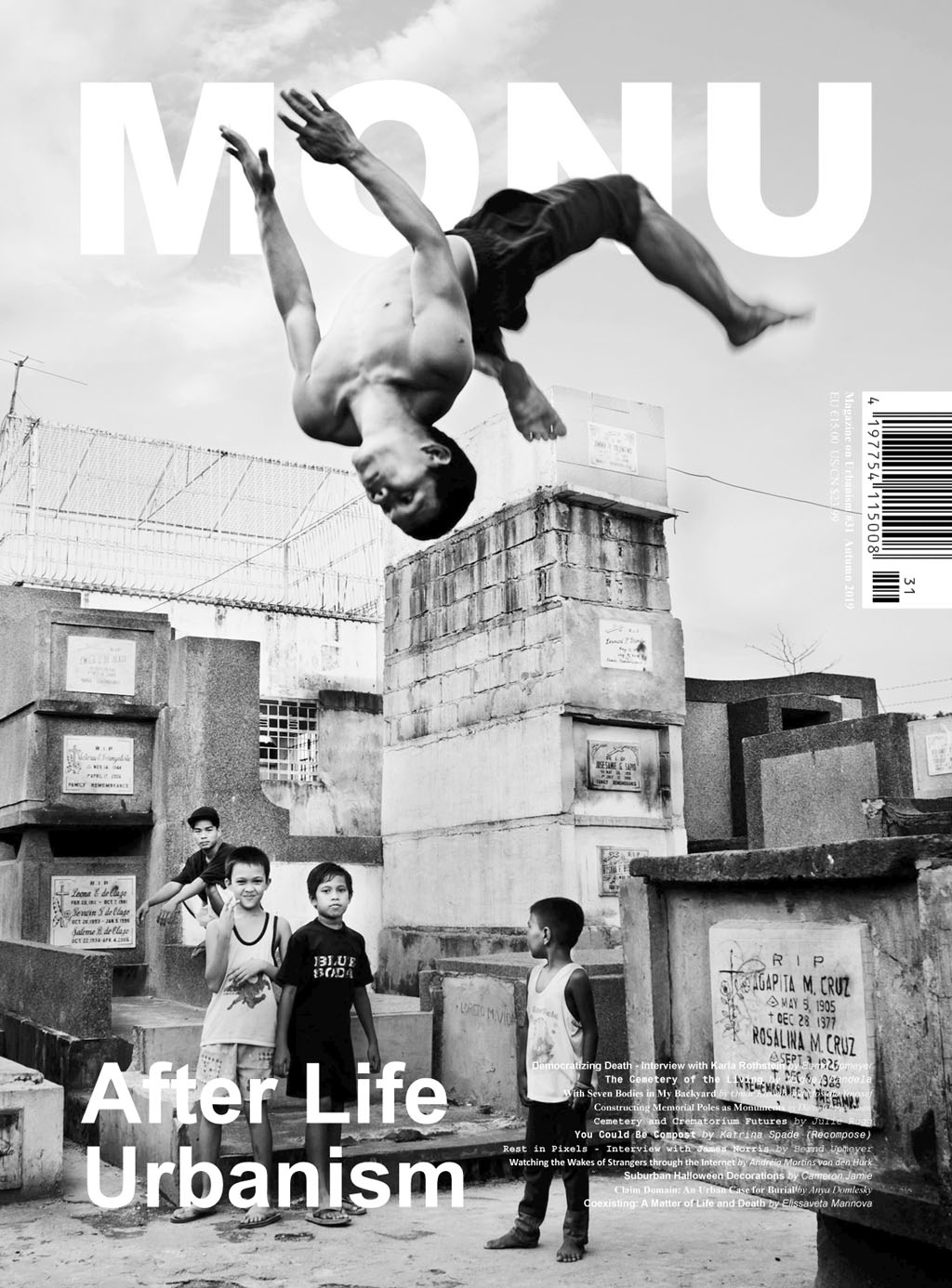

To face the urban challenges and phenomena that present themselves due to recent changes in our society that are related to death, and its consequences for cities and buildings, a topic that we call “After Life Urbanism”, “we need to be simultaneously pragmatic and visionary” according to Karla Rothstein in our interview with her entitled “Democratizing Death”. She urges the re-engagement and coexistence with life and death to explore what impacts all these transformations might have, encompassing first of all spatial, but also cultural, social, environmental, technological, and economic aspects. With his images of cemeteries of the city of Manila in the Philippines, where families do not tread in fear of the “wrath” of the dead but some found a place to call home among the crypts of the dead, Miguel Candela depicts and symbolizes in his contribution “The Cemetery of the Living” such coexistence of life and death. Omar Kassab and Mostafa Youssef take this thought even further in their piece “With Seven Bodies in My Backyard” arguing that the idea of the cemetery as an apparatus of isolating death, as a form of escapism from the reality of our own mortality, is deemed obsolete and propose to eradicate the cemetery as a territorial land-use entirely, dispersing it throughout the city leading to a dissolving of the cemetery. How places for mourning can be scattered around the city is demonstrated by David Charles Sloane in his piece “Constructing Memorial Poles as Monuments”, suggesting to use poles, trees, and fences as “Everyday memorials” in the public realm. That could be an innovative way to approach the problem that in the near future many urban cemeteries will fill up, and few have room for expansion. However, Carlton Basmajian and Christopher Coutts see human burial, with an emphasis on natural burial instead of cremation and the burying of embalmed bodies, as a vehicle for long-term land conservation and restoration, and for an emotional reconnection to the eternal rhythms of life, death, and remembrance, as they put it in their article “Death and Burial: In the Past Lies the Future”. According to Julie Rugg cemeteries contribute to the city a unique kind of landscape that is highly beneficial to mental health as these are places where it is not regarded as unusual to be solitary, and to enjoy quiet reflection, contributing emotional intelligence to the cityscape, as she argues in “Cemetery and Crematorium Futures”. But as long as humans continue to be buried in the ground, whether in a beautiful and meaningful way with intentions of “placemaking” or not, urban challenges and limitations such as the creation of affordable housing or the construction of dense and compact cities, to name just a few, will remain, and will require new ideas. One pioneering approach might come from Katrina Spade and her company Recompose that offers trailblazing burial and cremation alternatives having developed a system that transforms a body into soil in approximately one month as a new sustainable death-care option that has been legalized in Washington State recently, as is explained in her contribution “You Could Be Compost”. That technology can also introduce creativity to the discussion is revealed by James Norris, who is the founder of the end of life planning software “MyWishes”, in our second interview entitled “Rest in Pixels”. On MyWishes users can plan for death, their funeral, can say their final goodbyes, and post pre-designed content, such as updates, pictures, and comments, at defined intervals or on certain important dates or anniversaries after their death. That information technology, especially in the shape of the Internet, can lead to a broader cultural shift in dealing with death and dying, contributing to the creation of both new and alternative forms of sociability, is shown by Andréia Martins van den Hurk in her text “Watching the Wakes of Strangers through the Internet”. She thinks that people follow virtual wakes and live-streamed funerals mainly out of curiosity and thus considers an interest in death, dying and its rituals as part of human nature. Cameron Jamie documents this interest quite clearly in his photo-essay “Suburban Halloween Decorations”, where he depicts the elaborate Halloween decorations in his old neighbourhood in Los Angeles. With the images that show front lawns adorned with skeletons, witches, pumpkins, and coffins he invites the spectator into the hinterland of death while also celebrating with a certain humour its position over that of life through festive engagement, in which death becomes a catalyst for remembrance of life. When dealing with “After Life Urbanism” a sense of humour can never harm, since “it’s tough dying these days” particularly as burials in an urban area are often very expensive, as Anya Domlesky points it out in “Claim Domain: An Urban Case for Burial”. Cost-cutting strategies can be found in Japan, where temples, such as Ruriko-in Byakurenge-do in Shinjuku, feature locker-style columbariums with high-tech vault systems for up to 7,000 urns, as explained by Elissaveta Marinova in her article “Coexisting: A Matter of Life and Death”. Apart from saving space the Ruriko-in Byakurenge-do temple bears additionally multiple uses that are all quietly coexisting with one other, something that has a tradition in Japan, where once temples were not only a place of prayer and training, but also a school, hospital and a cultural complex of a museum, concert hall, or library. But following Marinova, such progressive projects can only happen if architects, city planners and policymakers alike address the urgency together and break the taboo by design. Looking beyond the overcrowded, segregated cemetery will mean a wholesome overhaul of our public spaces and a complete reconsideration of the way we accommodate and remember the dead – and as Rothstein says, “make them more part of everyday life”.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2019

(Cover: Image is part of Miguel Candela’s contribution “The Cemetery of the Living” on page 16. ©Miguel Candela)

Find out more about this issue on MONU’s website.