10-12-21 // INTERVIEW WITH MABEL O. WILSON

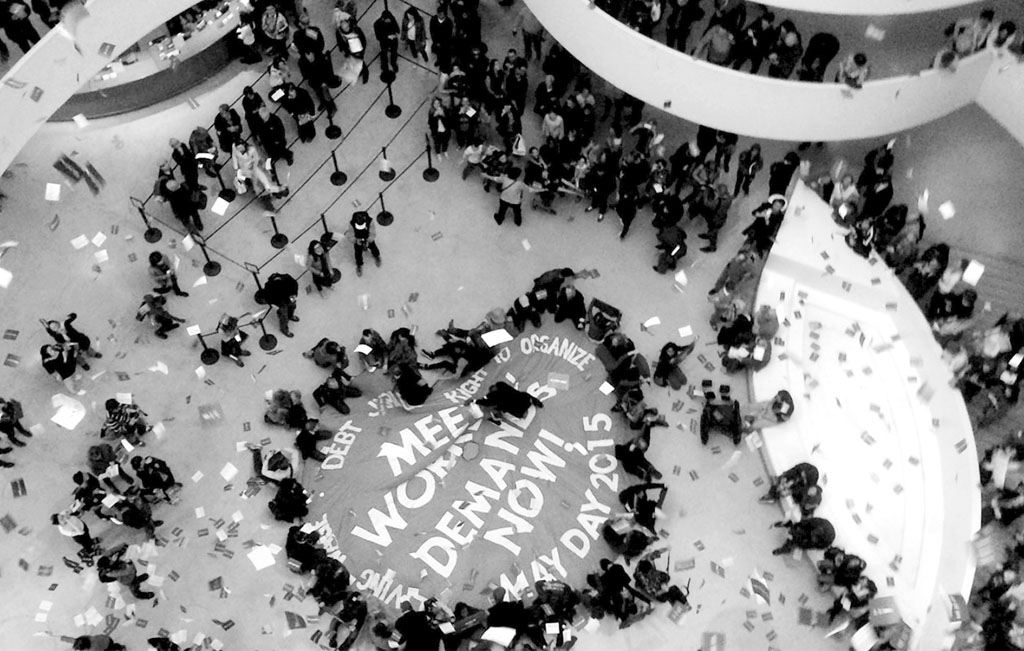

May Day occupation of the Guggenheim by the Gulf Labour Coalition, New York City, 2015

Photo by Gulf Labour Coalition

Bernd Upmeyer spoke on behalf of MONU Magazine’s Protest Urbanism-issue with Mabel O. Wilson, who is the Nancy and George Rupp Professor of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, a Professor in African American and African Diaspora Studies, and the Director of the Institute for Research in African American Studies (IRAAS) at Columbia University. Through her transdisciplinary practice Studio&, Wilson makes visible and legible the ways in which anti-black racism shapes the built environment and how blackness creates spaces of imagination, refusal, and desire. Her research investigates space, politics, and cultural memory in black America; race and modern architecture; and visual culture in contemporary art, media, and film. Wilson co-organized with Sean Anderson the exhibition ‘Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America’ at The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA).

Manifestations, Methods, and Strategies of Today’s Protests

Bernd Upmeyer: While urban protests featured in both of our last two MONU issues – in #32 on more affordable cities and in #33 on the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic for cities – but merely as a side topic, with this new issue of MONU we would like to focus entirely on protests as an urban phenomenon, as they appear frequently and intensely as an urban approach for change these days.

In a time when most activism is expected to take place in the digital realm and via social media – not only because of the coronavirus pandemic – such numerous mass-events in the physical spaces of our cities might come as a surprise, which intrigued us to such an extent that we decided to study them further. Why do you think mass-events and mass-protests are happening still today in the physical spaces of our cities and not merely in the digital realm?

Mabel O. Wilson: Social media monetised social relations. What used to be for the most part free social behaviour—conversation and friendship between individuals—is now mediated, monitored, and monetised by private transnational corporations like Facebook and Twitter. Thus how individuals and groups organise protests is still a vital public activity, even though the social media age marks a shift in form and forum. I would also argue that there is still some necessity and validity in having physical bodies in a public space, feet on the ground so to speak, in order for a protest to have an effect. And given recent protests around the world from Minneapolis to Hong Kong that fact does not seem to have changed. Bodies occupying large spaces or marching through different types of arteries – be it streets or freeways – still seems to be a central tactic for how people engage in forms of political protest.

BU: The reasons for recent social counter-movements all over the world have been well-documented, discussed extensively and are mostly related to fairer distribution of wealth and affordable housing, commercial, social and cultural spaces, and transport costs. But the current global Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality and racially motivated violence against black people make clear that the challenges at stake are even bigger. What distinguishes – according to you – the Black Lives Matter protests from other current protest movements in terms of their motivation?

MOW: All protests have their different origins and are created within different contexts of political power, diverse histories of nationalism, colonialism, and imperialism. All protests also have different agendas and aspirations. With that in mind I do not think that the current protests have a lot to do with what happened on Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring protest, and neither with Occupy. So I don’t think that they can be placed under the same umbrella, but each draws its motivations from its own histories and struggles and each of these histories has its own complexities. But there are through-lines that forge connections such as the fight against predatory corporate power and the violence enacted by the police and military, for example. When you look at the current Black Lives Matter protests, you can find traces that go back to the 1960s Civil Rights and Black Nationalist struggles against anti-black racism. But they are also related to post-colonial struggles after WWII to throw off colonial domination and exploitation. Today’s protests emerge from the histories of places where they occur. On the other hand one could also make the case that Black Lives Matter is very different from the civil rights movement because it is a different set of individuals and institutions that are leading the charge. BLM also fights against different articulations of white supremacy and police violence than the civil rights movement fought against. Today the deleterious effects forged by Jim Crow1 segregation on Black lives has morphed into new regimes of exploitation and de-humanisation such as mass incarceration. Since its inception in response to the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012 BLM has been remarkable in terms of how it has been able to sustain both its message and its impact as a protest movement.

… the complete interview was published in MONU #34 on the topic of Protest Urbanism on October 18, 2021.