17-01-25 // BEAUTY CAN STILL BE FOUND – INTERVIEW WITH AI WEIWEI

A recent photo showing the underground dugout, known as a “diwozi”, where Ai Weiwei and his family lived

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Ai Weiwei, who is a Chinese conceptual artist, documentarian, and activist. Many of his works are especially conflict-driven and strongly related to architectural, urban, and spatial topics, which we at MONU considered as particularly interesting to talk about in this issue on “Conflict-driven Urbanism”. Several of these projects were recently exhibited in the Kunsthal in Rotterdam under the title “In Search of Humanity”.

Life-shaping Conflicts

Bernd Upmeyer: With this new issue of MONU on “Conflict-driven Urbanism” we aim to investigate how conflicts shape and influence cities and buildings, and spaces in general, whether these conflicts are armed or unarmed conflicts. In an interview with The Guardian in 2021 you stated that the year you were born, your father, Ai Qing, a poet, was exiled being accused of “rightism”. Your family was subsequently exiled to Shihezi, Xinjiang, and only returned to Beijing in 1976 after Mao’s death. One might say that you were born right into conflicts. How did these early conflicts shape your life?

Ai Weiwei: The conflicts that I was born into arose from the cultural cleansing of diverse opinions and dissenting thoughts within a highly autocratic society. These conflicts in early-stage communist countries manifested themselves in a brutal and cruel manner. My father, a poet and politically exiled individual, was labelled anti-party and anti-socialism. This branded us as dissenting individuals in terms of class; the quality of our existence, all actions and thoughts, were subjected to strict censorship and surveillance, often triggering significant criticism. Yet, for me, this had a positive effect; it positioned me invariably on the opposite side of mainstream culture. I was acutely aware of our difference from mainstream culture, and even if conformity was desired, it was not permitted. Consequently, I naturally became a rebel. I believe this has profoundly impacted my future work, fostering a suspicion of mainstream ideologies and an innate disdain for the masses and crowds and grandiose political ideals.

BU: In the same interview you describe the bleakest period of this early exile as the period when you, your brother, and your father lived in a dugout in “Little Siberia”, part of China’s far north-west. You mention that there your “bed” was a raised dirt platform covered with wheat stalks, with a square hole in the roof to let in light. How was it growing up in such a place?

AW: We lived in an underground dugout, known as a “diwozi.” It featured a small window in the roof, through which a ray of light entered. This small detail was profoundly informative. The walls of our dugout were very thick, matching the depth of the earth itself. That single ray of light became particularly captivating because, without it, we would have been enveloped in complete darkness. In such dire circumstances, I learned that beauty can still be found; it is inherently linked to the quality of our existence. This experience brought me a profound awareness.

[…]

Responsibilities

BU: More generally speaking, what function and responsibility do artists have and what role might they play in processes of conflicts that differ clearly from the function, responsibility, and role of architects, urban designers, and urban planners? What can we learn from artists when it comes to “Conflict-driven Urbanism”?

AW: Speaking broadly, artists engaged in conflicts can exhibit more personalized judgments, which are crucially important. In reality, artists are not burdened with ethical responsibilities, and these responsibilities cannot manifest themselves in aesthetic expression. Meanwhile, architects and urban planners often play the role of hired hands and typically lack moral awareness. They are primarily engaged in optimizing the projects of those in power. This type of optimization, under most circumstances, contributes to disaster.

BU: Since conflicts must not always be destructive, but can indeed be constructive too, how do you think cultural producers such as artists, architects, and urban designers can contribute positively to the resolution of conflicts in a more effective way?

AW: Under most circumstances, conflicts cannot be definitively classified as either destructive or constructive, as every conflict inevitably results in some parties benefiting while others suffer the consequences. This dilemma is an unavoidable aspect of human development. I do not believe that artists, architects, designers, or producers can make any direct contributions to resolving these issues. As a human being, I think the greatest challenge lies in addressing the spiritual state of individuals within these conflicts. The goal should not be to become a casualty of conflict, but to treat other lives and living environments in a humane and benevolent manner…

… the complete interview was published in MONU #37 on the topic of Conflict-driven Urbanism on October 14, 2024.

The making of “Straight”, 2008 – 2012,

Image is courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, ©Ai Weiwei Studio

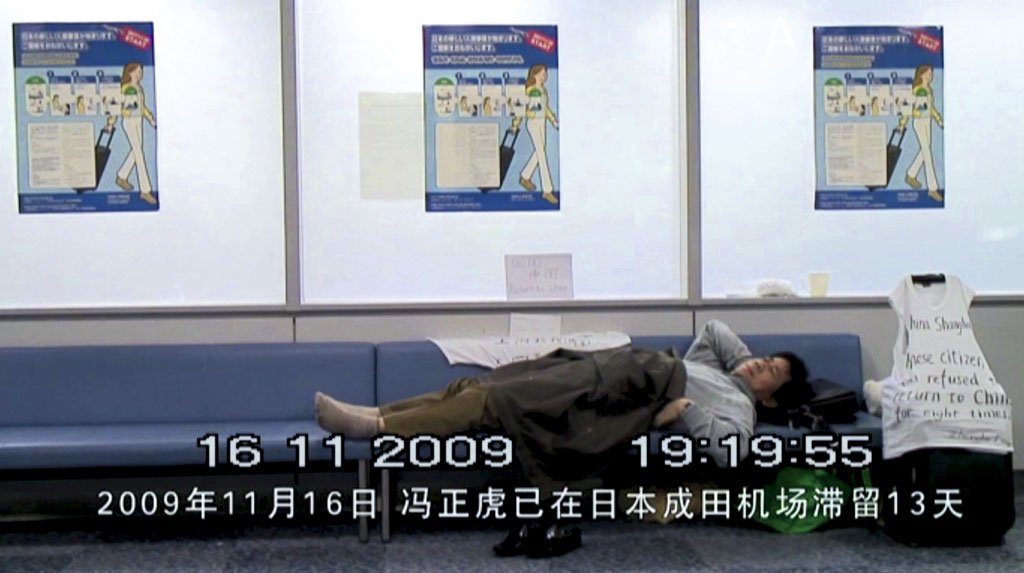

Film still of “A Beautiful Life”, 2010,

Image is courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, ©Ai Weiwei Studio

View inside of one of the six iron boxes of the S.A.C.R.E.D. installation during “Supper”,

Image is courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, ©Ai Weiwei Studio

Film still of the documentary film “Human Flow”, 2017,

Image is courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, ©Ai Weiwei Studio