16-10-23 // MONU #36 – NEW SOCIAL URBANISM

Vulnerable City by Maria Reitano; Free Floating Fascism and Religious Revanchism is The New Neoliberalism by Mark Gottdiener; Social by Definition – Interview with Sharon Zukin by Bernd Upmeyer; Density, Equity, and Epidemics in New York City by Richard Plunz and Andrés Álvarez-Dávila; Do Nothing for as Long as Possible by Tatjana Schneider; The Life Within Buildings: Towards a New Housing Policy by Christoffer Jusélius and Helen Runting; Unforgetting the Public City by Constanze Wolfgring; New Rights, New Needs, New Rules by Nuria Ribas Costa; Spatial Reappropriation through Transformative Practices by Valentina Rizzi; New I Am by Bharat Sikka; Post-Public Space by Francisco Silva; Technology as Medium to Rethink Spatiality by Tatjana Crossley; From the Global Village to the Global Home by Serafina Amoroso; 2091: The Ministry of Privacy by Maxime Matthys; The Strange Bedfellows of Contemporary Urbanism by Brian Holland; San Francisco: From “Ghost Town” to a New Social City? by Agnes Katharina Müller; Between the City and the Family – Interview with Izaskun Chinchilla by Bernd Upmeyer; The Opportunity for Joyful Cities by Paul Kalbfleisch; The Municipal Services Buildings of Hong Kong by Ying Zhou; Navigating the Work Morphology Shift: A New Perspective on Social Urbanism by Mingming Zhao

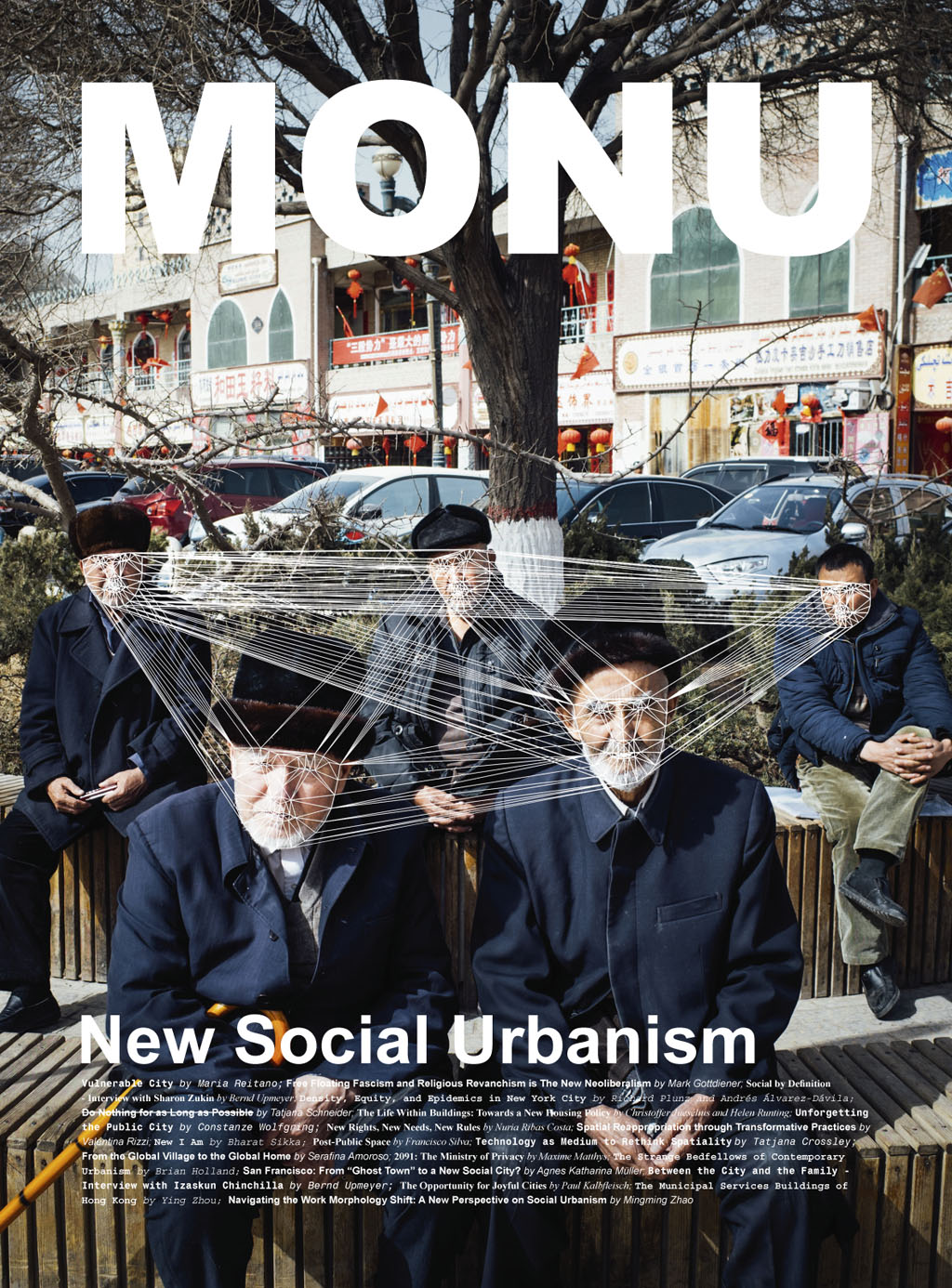

How is a “New Social Urbanism” possible if the hegemonic Western paradigm of space production revolves around the antisocial principle of the individualization of every aspect of life? asks Maria Reitano in her piece “Vulnerable City”. According to her, long before, during, and after the pandemic, individualization and competitiveness define the (anti)social consistence of the Western neoliberal city. Following Mark Gottdiener and his contribution “Free Floating Fascism and Religious Revanchism is The New Neoliberalism: Challenges for Architects and Urban Planners” we have entered a new phase of global destabilization amplifying social deficits after Neoliberalism’s dismantling of social institutions has been shown to have critically injured the structure of society leading to aggravated and extreme social problems. Sharon Zukin, too, is rather pessimistic about whether a “New Social Urbanism” is rising, as she states in our interview with her called “Social by Definition”, pointing out that even cities like New York are increasingly unable to pay for and to respond to people’s needs for housing, healthcare, and education. Richard Plunz and Andrés Álvarez-Dávila confirm the dire housing situation in their article “Density, Equity, and Epidemics in New York City”, in which they emphasize that, after numerous attempts, the economics of housing production in New York today shows no capacity for producing affordable housing and that the most recent health crisis has only aggravated pre-existing socio-economic and racial disparities in housing insecurity. However, Tatjana Schneider challenges us in her contribution “Do Nothing for as Long as Possible” to engage with what causes these conditions, arguing that the critique is there, the analysis too, and that there are therefore hopeful rifts and cracks. Because we already have many of the tools and the infrastructures needed to challenge the unequal, cynical, and anti-social system in which we operate as planners, as Christoffer Jusélius and Helen Runting clarify in “The Life Within Buildings: Towards a New Housing Policy”, but what we do not have – yet – is the collective will to fully utilize these resources. That is why we need to revive a sense of solidarity and shared responsibility, an ethics that constitutes a necessary foundation for the hard work that will be needed to create inclusive cities. Nuria Ribas Costa reminds us in her article “New Rights, New Needs, New Rules” that such ethics can be stimulated and supported by the implementation of collaborative and grassroots conflict-solving and decision-making institutions, as “New Social Urbanism” is not only about how the city is lived, but also how it is owned and governed. Thus, envisioning a “New Social Urbanism” requires a thoughtful consideration of participatory co-constructed strategies that revitalize the urban and social fabric, providing an organic pathway for community development, as Valentina Rizzi puts it in “Spatial Reappropriation through Transformative Practices”. Her research presents case studies that intervene in the urban realm by combining visual arts and performative arts with the architecture of bodies and spaces, aiming to create transformative experiences of rupture, experiences that are mysteriously graspable in the images of Bharat Sikka’s series of photos entitled “New I Am”. But today our urban realm and our public spaces have expanded due to recent technological progress into the digital domain too, enabling possibilities for human relationships that were once out of reach as Francisco Silva points out in “Post-Public Space”. According to him, social spaces can become places of reunion that are driven by a design focused on the complexity of the human connection. In a merger of body, technology, and all the structures that surround them, public spaces may finally find a tabula rasa that allows them to return to their very essence – the pleasure of connection. By uploading the photographs of the everyday lives of the inhabitants of one of the last remaining bastions of Uyghur culture in Kashgar into facial recognition software and by rendering the resulting biometric data directly onto the subjects’ faces, Maxime Matthys illustrates with his project “2091: The Ministry of Privacy” what such a merger of body, technology, and surrounding structures might look like. One way of understanding mergers like these is through the concept of hybridisation. To do so, Brian Holland introduces in his piece “The Strange Bedfellows of Contemporary Urbanism” practices to which he refers as “piggybackings” that at their best create surprising entanglements that provoke hybrid forms and programs of social exchange capable of promoting greater equity and diversity in the built environment. For Holland the piggybacking practices that he presents illuminate an important form of social entrepreneurialism in contemporary urban life contributing to a “New Social Urbanism”. When asked about the future of social urbanism, Izaskun Chinchilla, too, believes that we are heading toward a hybrid situation in which we will socialize both physically and digitally, multiplying the spectrum of the ways of meeting and socializing, as she explains in our second interview entitled “Between the City and the Family” stressing the importance of the neighbourhood for a “New Social Urbanism”. And as the demarcation between home and work increasingly dissipates, architects, urban designers, and urban planners might be motivated to conceive more “third spaces” in cities, which are public locations equipped with amenities to serve as communal workspaces, from parks and libraries to cafes and community hubs, as Mingming Zhao forcasts in “Navigating the Work Morphology Shift: A New Perspective on Social Urbanism”. She envisions a decentralized city, where technological progression and human comfort are intertwined, shaping an urban environment that feels simultaneously futuristic and familiar. We never know what new forms will emerge out of that, although if you think about democracy in a city as a role model, it is always very messy, as Zukin states, but according to her this may be what “New Social Urbanism” is all about.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2023

(Cover: Image is part of Maxime Matthys’ contribution “2091: The Ministry of Privacy” on page 84. ©Maxime Matthys; Music: Queen – I Want to Break Free, Video editing: Danae Zachariaki)

Find out more about this issue on MONU’s website.