09-12-21 // UNFINISHED URBANISM

La Pensée by Auguste Rodin, ca. 1895

Unfinished Urbanism

By Bernd Upmeyer

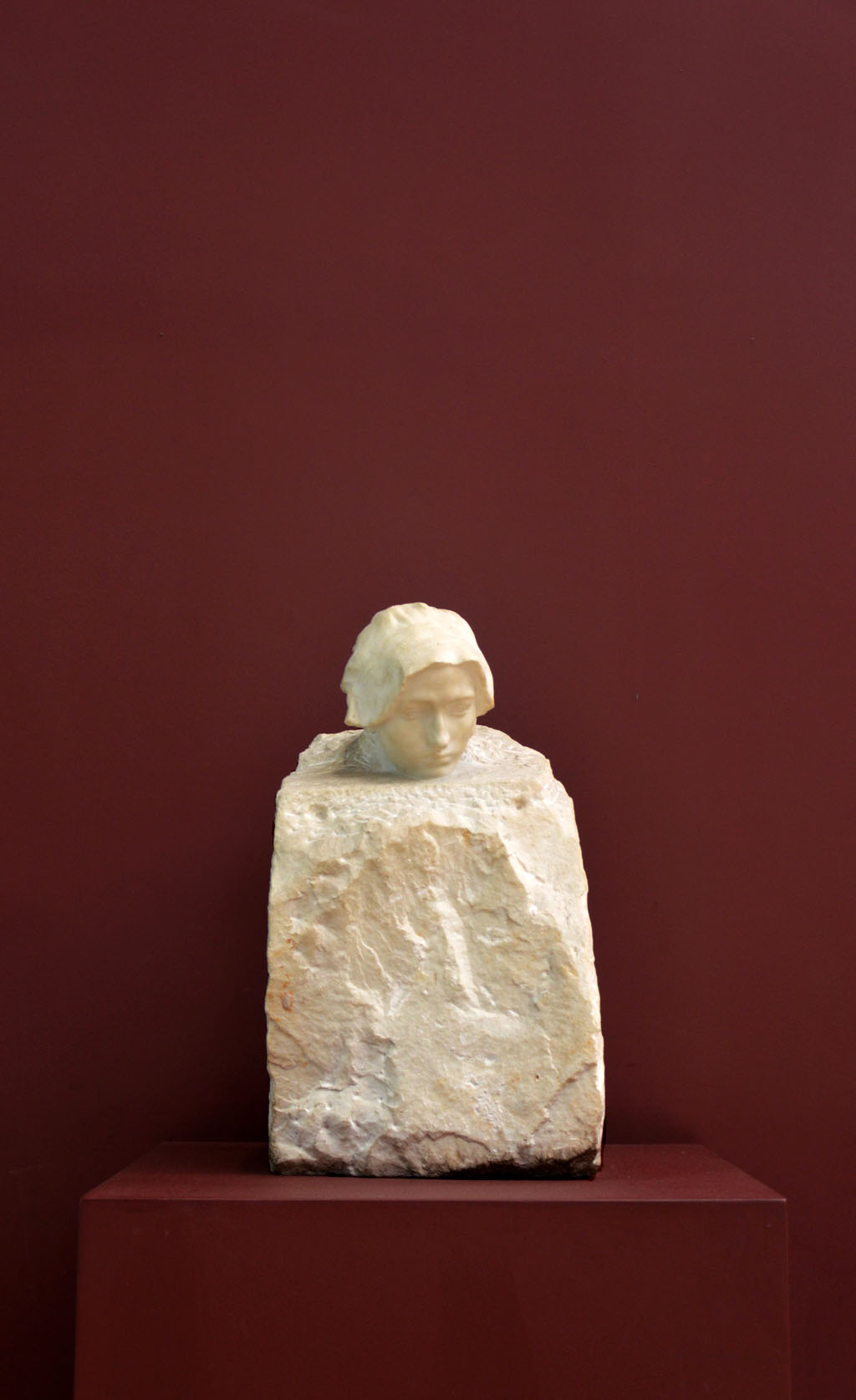

“Unfinishedness” is probably most strikingly represented in works of art. Just think of the Non finito-sculptures of Michelangelo made in the Renaissance-period that paid tribute to the theory of Plato that no work of art might ever completely resemble its heavenly counterpart. Michelangelo’s sculptures inspired the Non finitos of Rodin and his vague figures that appear to be struggling to emerge from masses of marble such as his La Pensée sculpture from the late 19th Century. Or picture the projects that were intentionally left unfinished such as the follies of the late 16th to 18th Centuries – such as the temple of philosophy at Ermenonville, symbolising that knowledge would never be complete – or imagine art movements such as Fluxus that during the 1960s engaged in experimental art performances which emphasised the artistic process over the finished product. Other artists that considered the process of creating more important than the finished work were creatives such as the American composer and music theorist John Cage who emphasised that one should embark on an artwork without any conception of its end. When thinking about contemporary expressions of unfinished creative work one might consider the designer Martin Margiela and his deliberately unfinished trousers and tops from his game-changing fashion show of 1989.

As rich and broad “unfinishedness” is applied and discussed in the world of art, music, and fashion, with this new issue of MONU we aim to investigate “unfinishedness” in architecture and urbanism. One of the most famous unfinished architectural structures is possibly Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família in Barcelona that has been under construction for around 140 years. Even with portions of the basilica incomplete to this day, it is still the most popular tourist destination in Spain with millions of visitors every year and one might wonder whether it is the “unfinishedness” of the building or the building itself that attracts that many people. Nevertheless, with this new issue we will not merely focus on buildings, but wish to address all kinds of different aspects of “Unfinished Urbanism”, from cities to regions to interiors, looking further than just the physical structures and the architecture into the economy, politics, ecology, and social aspects of cities, trying to find out how “Unfinished Urbanism” might be defined and figuring out its potential as well as its shortcomings.

Some of the potentials of “Unfinished Urbanism” might be found when describing cities as dynamic, flowing, creative, and as processes of transformation and ever-changing seemingly destined to remain “unfinished” forever. Consequently, according to the cultural theorist Ulf Hannerz, whom we interviewed for MONU #22, in order to keep culture going – and thus the production of architecture and cities as well – people as actors and networks of actors have to constantly reformulate culture, reflect on it, experiment with it, remember it, debate it, and pass it on. Following Matilde Igual Capdevila in the same issue, cities therefore need to remain in motion and in a certain state of “unfinishedness” continuously, reinvent themselves perpetually, in order to sustain themselves, which might lead to the fulfilment of our desires and cosmopolitan visions for a better future. Released from the pressure of ever being “finished”, “Unfinished Urbanism” might become a vital, active, and experimental practice that stimulates creativity and freedom of expression. The possibility to change and to remain unfinished might even be something that needs to be preserved when cities are becoming too static as Beatriz Ramo argued in MONU #14 that dealt with the topic of “editing” cities. Therefore, as stated by Matthew Johnson in MONU #13, cities should be allowed to exist in a state of permanent upgrading and renovation – always unfinished and under scaffolding, in the form of a transactional urbanism – to continue being able to alter and to remain flexible.

However, what is appealing as a theoretical concept, especially when it comes to flexibility and adaptability related to change, might not necessarily work for unfinished buildings or other architectural structures such as bridges and roads where construction work was abandoned or on-hold at some stage, as this can have tremendous negative consequences on the economics, social life, safety, the environment, and in many cases the functioning of cities. Uncompleted and abandoned property might become hideouts for criminals, lead to the reduction in property values within the vicinity or neighbourhood, reduce the aesthetics of entire city quarters leading to blighted urban areas, increased environmental problems, and is a waste and underutilization of urban resources in general. Despite some success stories – such as the provision of affordable shelters for artists or the urban poor in unfinished buildings – most unfinished structures remain as symbols of decay in our cities, often leading to further challenges.

Unfinished structures can be found all around the world making “Unfinished Urbanism” a truly global topic. The most common reasons for their presence are based on economic factors. But buildings and entire city quarters have also been stranded in limbo by wars, political factors, epidemics, inadequate planning, natural disasters, unforeseen structural weaknesses, and other unpredictable obstacles, leaving partial structures as haunting reminders of what might have been. In developed countries one might consider the situation in Greece, where unfinished buildings are a fairly common sight. But unfinished buildings occur particularly often in cities in developing countries and heavily indebted countries, where developers struggle to obtain loans, but nevertheless start building hoping to tempt buyers to put down deposits. In some African cities such as Dakar in Senegal people rather save their money in physical structures and concrete, tying up capital for years in unfinished buildings, than putting it into a business or bank, which they distrust. And investments in buildings often escape the notice of African tax collectors, since enforcement is weak. Furthermore, weak property rights, fluctuating prices of materials, flaky contractors, or money laundering leads to thousands of unfinished buildings in cities in African countries such as Nigeria.

Therefore, with MONU #35 we would like to find out what “Unfinished Urbanism” may mean today. What does “Unfinished Urbanism” look like, what are the reasons for it and what consequences might it entail for cities, neighbourhoods, buildings, and interiors, both positively and negatively? At which scale does it work best – on the urban scale, the scale of buildings, or the scale of interiors? How can we design the “unfinished” in cities and buildings to profit from its prospects and to limit its weaknesses? How does “Unfinished Urbanism” differ between cities of different countries and continents all around the world? Could there be an urban Non finito that might be able to help improve our cities? How should “Unfinished Urbanism” be used as a strategy for better cities in general, now and in the future?

Title: Unfinished Urbanism

Author: Bernd Upmeyer

Date: December 2021

Type: Call for Submissions, MONU #35

Publications: MONU – Magazine on Urbanism

Publisher: Board Publishers

Location: Rotterdam, The Netherlands